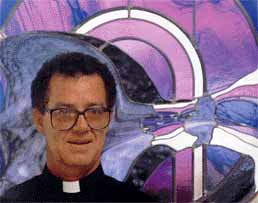

Father Dan Hillen, Stained Glass Artist

by Karen E. Davis

It was 1947 in Butte, Montana, and four-year-old Dan Hillen spent his days mesmerized by the antique glass bottles from the shed next door: Day after day he played with them, lining them up in rows by color and density…

To understand Father Daniel Peter Hillen and his art, one must go back to his hometown. Dan Hillen is a Butte boy. More specifically, he is an Irish-Italian Catholic Butte boy and the son of a miner. In Montana that sentence would say it all; Montana is a state with more than enough room under its wide-open skies for characters and eccentrics. Butte is a company town and a Catholic town, a town physically dominated by the Continental Divide and the huge open-pit copper mine of the old Anaconda company. In a state that worships individuality, Butte is still larger than life.

photo by John Reddy

Hillen's father was a miner and later a shift boss, a man who made his living in the dark caverns of the earth. His son's life would become a step more primordial--stained glass, the distillation of light and melted sand. Hillen was ordained to the priesthood of the Roman rite in 1969 and received a Masters in Divinity from St. John's University in Minnesota. Hillen is a man who took the priesthood and his faith and married both to his glass art; along the way he taught college for more than 20 years at his alma mater, where he earned his first of four degrees: a B.A. in Philosophy.

Thus far, Hillen's life has still had two specific high points: the year he spent restoring the German glass in his own diocese at the Cathedral of St. Helena and the creation and eventual destruction of his 12 stained glass fictional Life magazine covers.

Hillen remembers "always being an artist." As a child he vandalized his prayer missal by filling the blank pages with drawings. Years later he would gain a BA in Fine Arts from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design and an MFA from the University of Montana as well as post-graduate study at Pilchuk in Seattle.

His journey into stained glass began when fate combined with a winter storm and an unfinished art project. In 1974, it was snowing when Hillen visited a Minneapolis hardware store. He was trying to wrap up a class project to make the alphabet in 26 different media. The store was already closed; he waited out a storm across the street, at Gaytee Stained Glass Studio.

Fascinated by "a back room full of old men soldering and smoking cigarettes," he went back for three straight days "to just stand and watch." The third day he bought enough glass to make the letter 'T' for his upcoming exhibition. Twenty-two years later, Hillen has become the artist that Richard Mesmer of Seattle, a former Financial Secretary of the Stained Glass Association of America, salutes as a "Renaissance man and a national treasure."

Mesmer met Hillen in 1982, when he heard about "this priest who was attempting to restore the glass in the Helena cathedral." The cathedral, built at the beginning of the century, contains 56 hand-painted windows by the world-renowned F. X. Zettler of Munich. Admittedly opinionated, Mesmer asked himself what in the world could a priest know about stained glass and how big a mess was he making? He traveled to Helena, convinced that Hillen must be discouraged from undertaking the project.

Hillen, who studied under Albinus Elskus, set to work with scaffolding and binoculars. This would be the first professional restoration since its installation 55 years earlier on glass valued at close to $16 million and considered to be one of the finest art collections in the state. The full project--surveying, cleaning, repairing--would take a year of Hillen's life, closing the cathedral down for six months in mid-1982. Much of the damage to the glass happened during a major earthquake in 1935. In addition, someone entered the church armed with a gun and shot out several sections.

Some of the patch jobs he uncovered are the stuff of legend. Hillen would eventually discover 122 broken pieces that had been patched with regular window glass and touched up with house paint.

"This guy can absolutely do it all-and better than most," Mesmer comments. "He is way ahead of his time ... when does this man have time to hear confessions?" Mesmer remembered his original opinion that "I thought this guy couldn't possibly be authentic to the original (glass). I was wrong. He was determined to do it right."

"It was an immense honor, because I'm so connected to that building," Hillen added. "I have celebrated the sacraments there, and we use the church for our graduation Mass. St. James in Seattle is the closest cathedral, and it does not compare to the rich beauty of ours. Even the stained glass in Votive Kirche in Vienna, which our cathedral is modeled after, doesn't compare. The glass in the Cathedral of Saint Helena is one of the finest examples of the Romantic painting style coming from Europe."

Three years later, Hillen saw a national news story about the Ethiopian famine and that country's current leader's $250 million birthday party, juxtaposed between cat-food and low-fat cereal commercials. "It was too painful to ignore," he remembers. His next defining work, the Life series, was born.

Over a period of four years, Hillen produced a dozen giant, fictional Life covers (48"x34"). His painful horror at the newscast "needed to be more permanent. I decided a magazine cover would be the best vehicle." The issues addressed include the environment, German concentration camps, Vietnam, John Lennon and the Cherokee's Trail of Tears, all coming together, illustrating the constant ironies surrounding life.

A series born of horror and irony became true to its heritage. Life magazine heard about the series--and threatened legal action for trademark, infringement. Hillen's lawyer argued First Amendment commentary; the magazine threatened more legal action. After showing the series in Helena in 1989, Hillen packed it away in his studio for more than five years. "It was a very painful legal dialogue, and I was more than depressed," he added.

The series sat until last year, when galleries in Montana chose to exhibit them despite possible legal repercussions. Recently shown a half-dozen times, the series was destroyed last March in a car wreck.

Hillen winced at the still-painful memory. "As someone wrote to me, these are your 'Stations of the Cross,'" he said. "They were my children. I have an excellent video, great slides and wonderful memories."

Hillen is someone who fits the stereotypes of neither a priest nor an academic. He came to a recent interview wearing a Picasso T-shirt and a scraped knee covered with a cartoon band-aid.

"There are two ways to make art," Hillen said, swinging into a lecture. "You solve someone else's problems or you solve your own." Living in isolated Montana, Hillen is relatively self-taught. Long before the advent of machines which can cut difficult shapes, Hillen taught himself to do it by hand. "I hate unnecessary lead lines. Every line in the panel should be part of the overall design and not call attention to itself. In realistic works, if the lead lines interfere with the design, then I think the designer has failed. I feel my strengths as an artist come from a strong sense of design and color."

"I like the palettes of antique mouth-blown glass," Hillen observed. "Johannes Itten once said that 'Every color is a universe unto itself.' There's no such thing as a bad color. Sometimes it's just not the right day for that color. The medium itself is so beautiful that I sometimes feel guilty cutting a sheet of glass. It took other artisans to make the material--it takes great craftsmanship to blow the cylinders and cut it open and give it to us. It's a long process of craft and art."

Not just dependent on the craft of a glassblower, Hillen noted, stained glass also depends on sunlight. "It is in fact the only medium totally dependent on light," Hillen continued. "When the light disappears, the art dies. This art is ever changing, like life itself."

"My art is more than a single style. I work in realistic as well as abstract and non-objective styles. Glass is a visual language... a dialogue. I believe we as artists have a responsibility to society. We have to never stop telling our collective stories in new ways. We can challenge our viewers by humor, by anger, by fear and by faith. We are the only group given communal approval to do so. Historically, glass was a rather polite medium, designed to delight the eye. I think we are just starting as glass artists to challenge our society. I try to do that. I feel that the visual language of abstraction in glass can lead us to deeper spiritual experiences than perhaps realistic images did in the past.

"So is the glass medium or message? Maybe it's both, waiting for the sun to dance with it," Hillen observed. "The medium itself is so technically complex and takes a long time to master. I remember being at a conference once where everyone was talking about 'form and technique,' and I wanted to talk about 'content.' You can talk about how a work was created for only so long, and then you have to ask 'What meaning does it have?'"

Mesmer agrees. "Being isolated up there has forced him to be creative. He learns and works until he gets it right. I think his work is far superior to anything Andy Warhol did, and I think he's ahead of his time. He's not afraid to learn and to learn from others. He's totally committed at all levels of his art."

Mesmer evokes two names to make a final point--Leonardo da Vinci and Dale Chihuly: "Da Vinci wasn't fully appreciated while he was alive, and I don't think Hillen will be appreciated until people take him in context for what else was going on around him. For what Chihuly is in the hot glass world, I think Hillen is equally as gifted in the art glass world. He is so good, he is his own competition. His light burns strong. He is his own little treasure."

A final thought from the good Father: "My spiritual side is very much connected to the aesthetic side. In the absence of serious conflict in my life over those two issues, I have probably the best job on the planet. It is such a joy to create with a design that seems to come out of nowhere but really comes from a deep well within."